Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park

| Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park | |

|---|---|

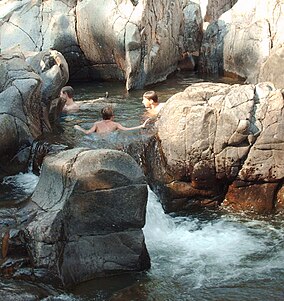

A portion of the park's natural water park pictured after the 2009 reopening | |

| Location | Reynolds County, Missouri, United States |

| Coordinates | 37°32′14″N 90°51′01″W / 37.53722°N 90.85028°W[1] |

| Area | 8,780.51 acres (35.5335 km2)[2] |

| Elevation | 1,106 ft (337 m)[1] |

| Designation | Missouri state park |

| Established | 1955[3] |

| Visitors | 373,204 (in 2017)[2] |

| Administrator | Missouri Department of Natural Resources |

| Website | Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park |

Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park is a public recreation area covering 8,781 acres (3,554 ha) on the East Fork Black River in Reynolds County, Missouri. The state park is jointly administered with adjoining Taum Sauk Mountain State Park, and together the two parks cover more than sixteen thousand acres in the St. Francois Mountains region of the Missouri Ozarks.[4]

The term "shut-in" refers to a place where the river's breadth is limited by hard rock that is resistant to erosion. In these shut-ins, the river cascades over and around smooth-worn igneous rock, creating a natural water park that is used by park visitors when water levels are not dangerously high.[5]

Geology

[edit]The bedrock of the area is an erosion resistant rhyolite porphyry and dark colored diabase dikes of Proterozoic age. Waters of the East Fork Black River became confined, or "shut-in", to a narrow channel following fractures and joints within the hard igneous rock. Water-borne sand and gravel cut deeply even into this erosion-resistant rock, carving potholes, chutes and canyon-like gorges.[6]

History

[edit]Precolonial history

[edit]The Osage Nation hunted in this area.[7]

After colonization

[edit]The park was the mid-19th century homestead of the Johnston family, Scotch-Irish immigrants who had moved west from the Appalachian region. There is a Johnston cemetery on the grounds, where 36 members of the family are buried (the "t" was later dropped from the name). [8]

When the Johnston family sold the land three generations later, most of it was purchased by Joseph Desloge (1889–1971), a St. Louis civic leader and conservationist. Desloge assembled most of the park, including the shut-ins and two miles of river frontage, over a period of 17 years, then donated it to the state in 1955.[9] The Desloge lead mining family continued over the years to donate funds for park improvements.

2005 reservoir failure and flood

[edit]On December 14, 2005, the park was devastated by a catastrophic flood caused by the failure of the Taum Sauk pumped storage plant reservoir atop a neighboring mountain. Damage included eradication of the park's campground, which was unoccupied at the time. The only people at the park were the park's superintendent and his family, who survived, sustaining some injuries. The park was closed because of the extent of the damage it received.[10]

The park partly reopened in the summer of 2006 for limited day use, but due to dangerous conditions, swimming in the river and exploring the rock formations was prohibited. In 2009, the river and shut-ins were reopened for water recreation. A new campground opened in 2010.[11] Park restoration and improvements were funded with $52 million of a $180 million settlement to the state from AmerenUE, the owner and operator of the failed reservoir.[12][13]

2009 derecho

[edit]Some areas of forest in the park and the surrounding region were severely damaged by the May 2009 derecho windstorm. Straight-line wind speeds in this part of Reynolds County reached 60 to 70 mph (97 to 113 km/h) with microbursts estimated up to 100 mph (160 km/h).[14]

Activities and amenities

[edit]Park activities include camping, hiking, swimming, and rock climbing.[4] Park trails include a paved quarter-mile walkway to an observation deck overlooking the shut-ins,[15] the ten-mile (16 km) Goggins Mountain Equestrian Trail loop, and a section of the Ozark trail.[16]

An extension to the park provides an auto tour that passes by the ongoing recovery effort, as well as the recovered endangered fens area,[17] terminating at a shaded overlook of the flood path accessible from the park entrance. From this one can walk a path through the boulder field created by the flood. The boulder field contains many examples of the minerals and rocks that make up the St. Francois Mountains of the Ozarks.[16][18]

Goggins Mountain

[edit]Goggins Mountain is a summit in northeastern Reynolds County in the U.S. state of Missouri. The summit is at an elevation of 1,483 feet (452 m).[19]

The mountain lies within the northwestern portion of Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park.[20]

Goggins Mountain has the name of the local Goggins family.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: Data Sheet" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. November 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "State Park Land Acquisition Summary". Missouri State Parks. August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ a b "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park". Missouri Department of Natural Resources. December 10, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: River Levels". Missouri Department of Natural Resources. May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ Beveridge, T. R., Geologic Wonders and Curiosities of Missouri, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, 2nd ed. 1990, pp 40–43

- ^ jennifer.sieg (March 6, 2015). "Park History". mostateparks.com. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "The History of Onondaga Cave". Missouri State Parks. Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ^ "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: History". Missouri Department of Natural Resources. March 6, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ "Ten-year anniversary of reservoir breach that flooded Johnson's Shut-ins state park". St. Louis Public Radio. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "Mo. set to reopen Johnson's Shut-Ins Park in May". The Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau, Mo. April 15, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ "Settlement reached in Taum Sauk reservoir collapse". The Southeast Missourian. November 28, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "Gov. Nixon announces partial reopening of Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park on Saturday" (Press release). Office of Missouri Governor. June 5, 2009. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ "May 8th 2009 Derecho". National Weather Service. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: Accessibility Information". Missouri Department of Natural Resources. February 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: Trails". Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ "Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: Natural Features". Missouri Department of Natural Resources. April 7, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "Scour Trail at Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park" (PDF). Missouri State Parks. Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park

- ^ Missouri Atlas & Gazetteer, DeLorme, 1998, First edition, p. 56, ISBN 0-89933-224-2

- ^ "Reynolds County Place Names, 1928–1945". The State Historical Society of Missouri. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park Missouri Department of Natural Resources